“Be the change you want to see in the world.”

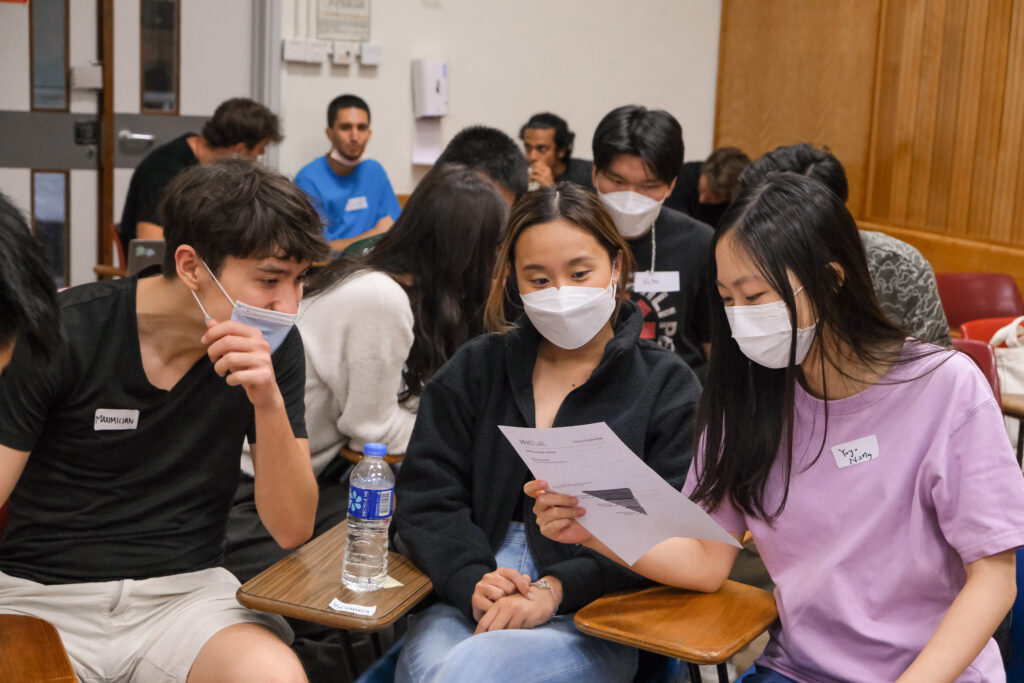

At the last Impact Lab Seminar on Systems Change, students were asked to define their understanding of “changemaker”.

Contrary to the students’ answers, including “Someone who is truly motivated to change the world” and “Someone who is brave enough to change themselves”, David Bishop, instructor of the Impact Lab Course, offered a different perspective. “The term changemaker is bullshit because no one who claims to be a changemaker is willing to break their system. The reason is that those who are able to call themselves changemakers usually benefit from the current situation.”

Do We Need Systems Change?

The term “systems change” is ubiquitous nowadays. But do we need systems change? And if we do, where is it needed?

Over the past few decades, the growth in global population, the expansion of standardized industrial technology infrastructure, the great acceleration of economic activities, the expansion of market system around the world, the advent of information technology and the global telecommunications network that interconnects billions of people all cumulate to the complex systems that interlink every aspect of modern daily life today.

The issue here is that our traditional way of thinking and organizing renders us ill-prepared to understand, design, and manage these complex systems. And because we are all part of these systems, our individual actions accumulate and affect the systems on a macro level, leaving our supply chains, food systems, energy systems, political organizations, and financial systems fragmented and dysfunctional.

That is why we are experiencing mounting crises today, including climate change, inequalities, catastrophic pandemics, power conflicts, threats to democracy, food insecurity, mental ill-health, disinformation etc.

To quote MIT Professor Otto Scharmer, who wrote in his book, Leading from the Emerging Future: From Ego-System to Eco-System Economies: “We collectively create results that nobody wants because decision-makers are increasingly disconnected from the people affected by their decisions. As a consequence, we are hitting the limits to leadership—that is, the limits to traditional top-down leadership that works through the mechanisms of institutional silos.”

And that applies to not just leaders but every one of us. “We often silo things into different categories, but that isn’t how the world works,” said David. “We need to look at systems change in a more holistic way. We need to think about the role of broad collaboration and how all actors in society work together and interact.”

Everywhere we look, systemic problems exist. There are six conditions that hold these intractable problems in place.

As a result, to drive systems change, we need to find out who gets to call the shots and make the rules, and how people think about or see a problem, so that we can change the power dynamics and beliefs.

How Do We Make Change?

The US Civil Rights Movement, spanning from 1954 to 1968 to abolish institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement, offers a good example to illustrate structural change, rational change, and transformative change.

The activists first looked at the mental models that held the structural problem in place: prejudice and stereotypes. They then identified the power dynamics, relationships and connections that perpetuated and worsened the problem: the lack of prohibitive policies against racial segregation and discrimination, and the lack of policies to promote equitable rights. Finally, they identified the structural elements that held the system in place: the common practice of segregating by ethnicity, prohibitive policies not being observed etc.

However, to enact change, you need people to join in your movement.

On 1 December 1955, when the US Civil Rights Movement was still in its nascent phase, African-American seamstress Rosa Parks was on her way home on a Montgomery Cleveland Avenue bus, sitting in the front row of the “colored section”.

At one point, all the seats in the “white section” were taken, and the bus driver asked Parks and three others to give up their seats. Parks was arrested, but she was bailed by a prominent African-American leader called E. D. Nixon, who decided that they would attack the segregation ordinance.

Meanwhile, a group of African-American women working for civil rights at the Women’s Political Council (WPC) started distributing flyers calling for a boycott of the bus system on 5 December, when Parks was expected to be tried in municipal court.

Soon, news of the boycott gained support from African-Americans in Montgomery, and on 5 December, about 40,000 African-American bus riders boycotted the bus system. The activists decided that they should continue the boycott until the city met their demand: the invalidation of the bus segregation laws.

And they were innovative with the ways to ensure the movement would last. For example, they organized carpools, African-American taxi drivers in the city charged the same as the bus fare for African-American riders, some chose to walk instead, and mass meetings at churches were held to mobilize more people to join the boycott. The movement almost bankrupted the city.

On 5 June 1956, the Montgomery federal court ruled that any racial segregation laws on buses violated the 14th Amendment to the US Constitution. In December that year, all buses in Montgomery were integrated.

The Critical Mass and Three Rules of Epidemics

The Montgomery Bus Boycotts illustrate that big, meaningful change typically happens when a group of people rapidly and dramatically changes the behavior by widely adopting a previously rare practice. The size of this group matters: To amass a “critical mass”, one would need to mobilize approximately 10% of the population.

There are generally three rules that govern how ideas and products spread in the world:

- Law of the Few: Connectors, mavens, and salesmen are the three types of people we need to initiate change.

- Stickiness Factor: How the message is spread.

- Power of Context: The conditions or contexts that determine how fast messages spread and therefore changes happen.

Why Are Systems Change Important?

At this point in the seminar, David asked the students this question: “If you had access to a time machine, would you want to live in any other period of time?”

Some students said they wanted to go back to the 70s, some further back to hunter-gatherer times, and some said they wanted to go 100 years back in time, before some political ideas were developed.

But jokes aside, it was clear that no one in their rational mind would choose to live in another era, because we are in the best possible era. To elaborate on his statement (which is aligned with Steven Pinker’s argument in his book, The Better Angels of Our Nature) David brought up the graphs that showed the global progress made in the alleviation of extreme poverty and falling housing prices in Hong Kong.

“Overall, the net welfare of humankind has never been better,” said David. “During our lifetime, there has been a great decrease in poverty all around the world, and India and China have improved significantly in this aspect. A lot of economic development in these countries has supported this change.”

Be the Change You Want to See

Equipped with the knowledge to drive systems change, students were put into breakout groups to identify the root causes and potential solutions for systemic problems, including racial discrimination, housing prices, and waste management in Hong Kong, as well as gun violence in the US.

Here, students were reminded of the system thinking approach:

- Look at the underlying issues.

- Think holistically: it’s the systems that create reinforcing feedback loops.

- Problems lie in how the system is structured.

So, how can we “be the change we want to see in the world”? An important first step is to understand what Mahatma Gandhi actually said in the quote that is often misattributed to him.

What Gandhi was essentially saying, according to author and transformationist Joseph Ranseth, is that in order to make effective change in the world, we must first do the inner work to “examine ourselves openly, honestly, vulnerably, and to purge out any resemblance of selfishness, depravity or insecurity”.

Mental clarity and resilience are essential to your work, whether it is candid self-enquiry or your continuous work to make the world a more sustainable and equitable place. Click here to learn how you can start building mental resilience today!